I recently revisited a magazine article I did on arranging over 30 years ago to see how germane it is to today’s world of scoring. Surprisingly, except for the fact that musical styles and industry practices have changed drastically (in the commercial advertising world we got paid to do demos and we recorded with live musicians), the basic tenants of presenting the fundamentals of arranging haven’t changed. Here’s an abridged and slightly updated version of that article.

BASIC TOOLS FOR BETTER ARRANGING

“As a young arranger, I was always searching for some work that actually described the process involved in making orchestral arrangements.“- Glenn Miller, 1943

Well, Glenn, we’re still looking for that one text that gives us the secrets and lays it all out for us. Unfortunately, that book will never exist, because arranging is an art that evolves hand-in-hand with music composition and technology; it is changing constantly. And, since it is an art, one can’t effectively break it down into hard rules and regulations. We can, however, list and explore the various musical techniques that one might use to get a working knowledge of the field. It doesn’t matter if you use a pencil and score paper or a mouse and a notation program, the principles and techniques still apply. “Okay, La Barbera, quit talking and show us some hip voicings.” Sorry Glenn, no voicings yet. So often, the novice assumes that the secrets of arranging lie in the chord voicings used by the various greats of the art. Nothing could be further from the truth. We have to learn what arranging is before we get to any of that. Here’s my definition of arranging:

Arranging, in music, is the art of giving an existing melody musical variety for a listening audience.

The composer gives us the melody and we, as arrangers, strive to give it variety. Henry Mancini has said, “The song is the thing, and the arranger’s function is to make it memorable, regardless of one’s personal feelings.” And variety, musical variety – is what makes the song memorable. This musical variety comes from our knowledge of the tools of arranging and how to use them. An arranger is very much like a magician. After presenting a melody to an audience we try musical sleight-of-hand to keep their attention, because if the audience can predict what’s going to happen next, we lose their attention and therefore are not as successful as arrangers. We’ll list some of those tools in a little while, but first I want to explain the last part of my definition – the audience.

As arrangers (or composers or performers for that matter) we are always dealing with an audience, whether real or imaginary. If we wrote or played music just for ourselves, it would not truly be a creative art. To be successful in the musical arts, one must always acknowledge the existence of a listener and create accordingly. It’s somewhat like the old riddle of “if a tree falls on your Pro Tools Rig in the woods and there is no one around to hear it fall, does it make a sound?“ Suffice it to say that with even one set of ears around, the whole event has an impact. It becomes memorable. I believe that the success of our great arrangers is partially due to their conscious or subconscious acknowledgement of a listening audience. So, if you think about it, the arranger’s job is to take a melody/song and play it for an audience for a certain length of time without boring them. If we played the same melody over and over with the same instruments for six minutes, with the same chord changes, they’d be searching for the rotten egg emoji. We have to give it variety and make it memorable so as to keep the audience’s attention. It’s just that simple. How we keep their attention shows our talent as arrangers. If we wanted to break down my definition into rules or commandments of arranging, we’d arrive at something like the following.

Rule 1: Thou Shalt Not Bore.

Strive to give the song or melody as much variety as necessary to capture and please an audience, while at the same time keeping the integrity of the composer’s musical idea. This is such a fine line – balancing one’s arranging techniques against the intent of the composer while maintaining a stamp of individuality – that it can take a lifetime to learn to do it consistently.

Rule 2: Know Thy Place.

We must always remember that, as arrangers, we’re subservient to the melody and must write accordingly. Unlike composers, we arrangers are not allowed the luxury of personal likes and dislikes when it comes to the melody or the musical style we have to work in. Disdain for a certain style or song shows through in your musical arrangement. (The hardest job I ever had was when Count Basie asked me to arrange Rubenstein’s “Melody In F” for his band. I didn’t care for the song as a Basie-style tune, and I stared at blank score pages for weeks.) We have to divorce ourselves from our musical prejudices, listen to all kinds of music, and be prepared to cover any style with sincerity. Remember what Hank Mancini said – “regardless of one’s personal feelings.”

Rule 3: Know Thy Boss.

Remember that we are ultimately working for someone else. When we take the job of arranger, we are not working for ourselves but for an audience with a composer or producer in between. We must strive to please both but fight like hell for the audience when confronted with a choice. I tell students that if I can get five percent of John La Barbera (a creative uniqueness or stamp of identity) in a chart, I’m more than pleased. The hardest pill to swallow is when you bring your finished masterpiece to a bandleader or producer and he/she immediately cuts out the hippest interlude you’ve ever written. All of us, no matter how famous we become, must be prepared to give up our most prized musical child at the whim of the client. The best advice I ever received from any arranging book was from Mancini’s Sounds And Scores [Cherry Lane]. I underlined the last paragraph on page 1 in my copy: ” … Finally, don’t fall in love with every note you write … Be prepared to eliminate anything that tends to clutter up your score, painful as it may be to do so.” Even if you are the composer /producer and it’s your record label featuring you as the artist, the audience is still the boss. Keep that in mind and you’ll find arranging decisions much easier to make. Now then, if you’re still with me, we’ll move on.

Rule 4: Know Thy Styles.

We must be familiar with the idiom in which we intend to place the melody. In simpler terms, if you have never listened to current pop styles like R&B, or Country Blues groove, etc., then you can’t successfully arrange a melody in those styles. Or, if you’ve never heard second line, you’ll be spinning your wheels when it comes time to cover that style. So, it’s obvious that if you aren’t familiar with a style of music, you can’t competently arrange in it. That seems pretty obvious, but I’ve seen students try to arrange a big band jazz chart who have never heard of Basie or listened to Stan, Woody or Duke. So, before we can become arrangers, we have to know our musical styles and learn what instruments, rhythms, and harmonies are basic to each idiom.

Now, let’s get down to the nuts and bolts of arranging by listing some of our tools and putting them in an arranging road case. These are what I call the five basic variations used in arranging, and we’ll get our roadie to pull them out one at a time and illustrate how each of them works. The devices in each category are just a starting point. I’m sure you’ll have your own ideas so add those as necessary.

RHYTHMIC VARIATION

1. Change the rhythm of the melody. Of course, no brainer.

2. Change the rhythmic feel; double time, half time etc.

3. Gradually speed up or slow down the tempo.

4 .Refrain from using one rhythm for any length of time.

5. Displace the melody relative to the bar line by a uniform value.

6. Change the meter 4/4 to 3/4. (My arrangement of “So What” is a good illustration)

Slightly varying the rhythm gives new life to the melody however, this is effective ONLY after you’ve stated the original.

The audience needs a reference before it recognizes a variation. I believe this is true for all of the variations we incorporate.

It’s been a common practice for years to go to double time for the blowing on a ballad and then back to the original tempo to take it out. Gradually speeding up and slowing down is a great device (Brad Mehldau and other groups have used this very effectively) but it takes some rehearsing.

Changing the meter is a great way to add variety. My arrangement of “So What” is a good illustration.

Then imply 4/4 and eventually get there.

The next tool in our road case is

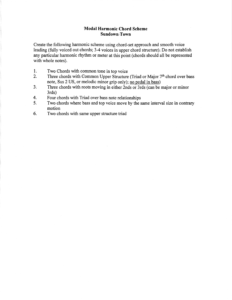

HARMONIC VARIATION

1. Substitute chord changes (reharmonization).

2. Change melodic modes (major to minor).

3. Use counterpoint to imply new harmonies.

4. Modulate to new keys, either subtly or drastically.

Every melody comes with its own harmony or set of chord changes, whether given or implied. If we change the harmony after our audience has heard and absorbed the original chord changes, we automatically create variety. So, the use of substitute chord changes, or reharmonization, is one device in the harmonic category. Another secret that seasoned writers share is that a new device introduced into the chart has effect, but the more devices or variations you add to a chart at the same time, the less impact each will have (i.e. modulating and using a substitute change for the new target key down beat…softens the impact). Keep this in mind when you are tempted to empty the whole road case of tools into the same section of a melody. As with all devices in arranging, we must remember that we are working for the song. Anything we add has to support the melody and not overpower it. I find that harmonic variation is the one tool that’s most overused by arrangers and is an area where we can get into the most trouble. Hip changes, used for the sake of being hip, rarely fit comfortably into a well-balanced chart.

Now that we have two arranging tools at our disposal. Let’s go on to another. I call the next device:

PERFORMANCE VARIATION

1. Vary the articulations of the melody.

2. Vary the dynamics of a phrase or section.

3 .Use ornaments, such as trills, turns, and grace notes.

4. Use pitch-bend or modulation.

5. Take advantage of the basic instrument mutes (plungers, straight mutes, hats, etc.) and combinations thereof (plunger wa-wa over straight mute, bucket over straight, cup in bucket, etc.).

6. Use effects that are unique to individual instruments, such as half valves, squeaks, flutter tongue, sub tone, etc.

Performance variations encompass quite a few items that we don’t always think of when doing an arrangement and, to me, is one of the most important tools we can use. I believe it’s what’s above & below the notes that make music and the uniqueness of an arrangement.

These are the performance techniques are the one uses when playing music – articulations (long, short, etc.), ornaments (turns, trills, shakes, flips, pitch-bend, vibrato, etc.), and dynamics (crescendo, decrescendo, subito p, sforzando, etc.). Using any of these performance devices in your arrangement is a sign of a seasoned writer. Just as an orchestra conductor studies all of the nuances of string bowing techniques, we must be familiar with all of the unique sounds and variances of each instrument in the band.

Mixtures of muted and open instruments is a wonderful way to add variety to an already stated melody…it adds color and the repetition of the melody is acceptable to an audience. The hat or derby is probably one of the most versatile mutes for brass but it has fallen out of favor these days. Muted brass in buckets produce wonderful colors. Look how a bone deep in the hat coupled with alto and trumpet creates a life like French horn sound at the end of the shout chorus.

Also, like Basie, using cresendi, subito p, and back and forth adds so much variety to the passage.

Here’s a link to the entire chart in case you want to check it out.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rZIA_zYlF_0

“What about chord voicings , aren’t you ever going to get to chord voicings like clarinet lead over two altos and two tenors?”

Sorry, Glenn, not yet. But that brings up an interesting point. People tend to interchange orchestration and voicing. They use the term voicing when they really mean orchestration and vice-versa. It’s very important to understand the difference.

When beginning students come to me with questions about arranging, the first thing they usually say is something like, “I’ve been working on this chart and I want to use this sax voicing but I’m not sure if it will sound.” Or, “Will this half step between the cellos and violas work?” This aspect of arranging, the voicing and orchestrating of chords , is just another tool in the art, but it always seems to attract the most attention. I guess it’s like a slick paint job on a Porsche – the most important parts are under the hood, but the paint job gets the attention, So, let’s clear this up right now. Voicing is the putting together of chords in a certain way, with the notes stacked in a certain order. Orchestration is simply what instruments are assigned to play the notes you included in the voicing.

VOICING

1. Close.

2. Open.

3. Cluster.

4. Unisons & Octaves.

Let’s talk about voicings. We all should know the difference between a closed voicing and an open voicing, a cluster and an octave unison. Voicing techniques, especially in jazz, are usually the individuality stamp of the arranger. I would voice and orchestrate a certain passage differently from my colleagues. If we’ve listened enough to any idiom we can probably pick out the individual arrangers by their style and voicing techniques. Traditionally, a composer/arranger would give a sketch of his or her work to an orchestrator, who, in turn, would use standard rules for assigning the different musical lines and chords to conventional bodies of instruments. In today’s music, there are so many new instruments, recording techniques, and consolidations of music styles that there are fewer and fewer standard rules of orchestration. So what was once a separate trade has now become an additional, necessary skill of the arranger.

To recap, the voicing is the type of chord structure (unison, close, open, octave, unison, cluster, etc.) and the orchestration is the body of instruments assigned to play the voicing. Orchestration and voicing allow us to create unique sounds or musical colors by combining different instruments. If we think of voicing and orchestration as two separate entities, it will be much easier to understand our job as arrangers.

On top of the endless possibilities and permutations of traditional acoustic instruments, we now have to contend with the modern instruments (world instruments, synths, samples, etc.). These new instruments are a challenge in themselves, and the combining of acoustic and electronic instruments gives us further combinations with which to achieve unique musical colors. We can truly spend a lifetime experimenting with voicing and orchestration, but it shouldn’t take the beginning arranger that long to find those combinations that fit and seem comfortable with his or her writing techniques. These combinations go toward making up an arranger’s style. For example, Nelson Riddle’s harmonic variation use of Lydian motifs identifies his work just as Gil Evans’ and Duke Ellington’s unique orchestration of their voicings identify their work.

Simply changing a line from unison to octaves gives it an entirely new character and an audience will accept the same backgrounds and chord changes. Here’s an example using my arrangement of “Esperanza.”

Here’s a link to full video of the chart in case you want to check it out.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UHN0FEgQRRY

There is one more device – melodic variation.

“Hey, that’s the composer’s job!”

Yes Glenn, sort of. Melodic variation, this last piece of essential equipment, is composition. The composer rarely gives us intros or endings. The arranger is usually expected to furnish those. We arrangers are also required to compose counterlines, interludes, and background melodies as well, in order to give existing material variety. Here are some thoughts worth pondering:

“Arranging, after all, is a euphemism,” according to Alex Wilder, “For it includes composition as well as orchestration. The introductions, countermelodies, transitions, and reharmonizing are all more than just orchestration. But by using the word arrangement, they get two skills for the price of one.”

“The true art of orchestration,” Walter Piston declared ,”is inseparable from the creative act of composing music.”

And from Nelson Riddle: “An arranger occupies, in music, that shifting, almost indefinable ground between an orchestrator and composer.”

MELODIC VARIATION

1. Creating and using countermelodies against melody.

2. Variation of melody or fragment of melody used for interludes between sections.

3. Introductions and endings based on newly created material.

It’s undeniable that arrangers must wear many hats in today’s music industry and must function sometimes as composers and orchestrators. That’s why arranging is not a hack trade but an art that takes years to perfect. So if you get discouraged because it doesn’t come to you right away, or, if after years of arranging, you still seem to get stuck, don’t worry; join the club.

About the Author:

John P. La Barbera is a Grammy® nominated composer/arranger whose writing spans many styles and genres. His works have been recorded and performed by Buddy Rich, Woody Herman, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Mel Torme, Chaka Khan, Harry James, Bill Watrous, and Phil Woods just to name a few. Though his major output has been in jazz, he has had works performed and recorded for symphony orchestra, string chamber orchestra, brass quintet, and other diverse ensembles. Most recently, Mr. La Barbera was chosen from among dozens of applicants to participate in the Jazz Composers Orchestra Institute at UCLA. As a result, John was one of sixteen composers commissioned by the JCOI to compose new works that meld jazz and symphonic music. “Morro da Babilonia” was the resulting work and was presented by the American Composers Orchestra in New York City at Columbia University’s Miller Hall. His “Drover Trilogy” for string orchestra and corno da caccia was recorded by the late Dr. Michael Tunnell and has recently been released on Centaur Records. John’s Grammy® nominated big band CD “On The Wild Side“ along with “Fantazm“ and his latest “Caravan” on the Jazz Compass® label, have been met with tremendous artistic and commercial success and are on the way to becoming a jazz big band standards. As co-producer and arranger for The Glenn Miller Orchestra Christmas recordings (In The Christmas Mood I & II) John has received Gold & Platinum Records and his arrangement of “Jingle Bells” from those recordings can be heard in the Academy Award winning film “La La Land.” Mr. La Barbera is a Professor Emeritus of Music at the University of Louisville’s School of Music and an international clinician/lecturer whose topics range from composing/arranging to intellectual property and copyright. Among his numerous organizational affiliations are Jazz Education Network, Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, NARAS, American Composers Forum, Chamber Music America, and a writer/publisher member of ASCAP since 1971.

John’s Sunday morning big band jazz radio show, “Best Coast Jazz” on WFPK has been a mainstay on public radio for over twenty years and is streamed worldwide. He is a two-time recipient of The National Endowment for The Arts award for Jazz Composition and has served as a panelist for the NEA in the music category. His career has recently been profiled in “Bebop, Swing and Bella Musica: Jazz and the Italian American Experience” and in dozens of publications and encyclopedias. John’s published works are considered standards in the field of jazz education.