Blog curator’s note:

In late May, I had been contemplating who I might solicit to write the July 1 ISJAC blog. I wanted to hear a voice different from the kinds of folks I had previously featured. Then I happened to catch this post shared by my friend Dominique Eade on Facebook: “I am the first African-American to earn a Master’s degree in Jazz Composition from UTA! #BlackHistory.” I thought, now that sounds like a story I’d like to hear, so I was delighted that Tatiana agreed to write something for us. Little did I know that 2 days later, George Floyd would be murdered by police officers not far from where I live in Minnesota and change all our lives (again) so strongly. So, in the midst of all that and this seemingly endless COVID crisis, I can’t think of a more appropriate voice for us all to hear from right now. My friends, Tatiana LadyMay Mayfield.

Backstory: Why Go Back To School?

It was February of 2018. I had just released my third album The Next Chapter a few days after my birthday and I wasn’t happy, but I should have been. I wanted to release it in February because of the ties to my personal life; my birthday, Black History Month, and my parent’s anniversary are just a few of the most important things about this month to me. However, I felt like everything about the project fell short except for the music after taking 4 years to complete it.

I spent the next few months trying to figure out what my next move would be while I continued to teach at Cedar Valley College in Lancaster, Texas and gig around town. At this point, I had been teaching voice for 8 years after graduating with my bachelor’s degree in jazz studies from the University of North Texas. During the course of that time, I toyed with the idea of going back to school to get my master’s degree several times but fear would always creep into the equation as well as the thought of more financial stress from dreaded student loans. I kept thinking to myself, “You’ve been away from school too long. It will be too hard getting back into the groove. Besides, what would you get your master’s in? Won’t this interfere with performing?” All I knew was that I wanted to open more doors financially for myself so that I could continue making the music that I love and share that passion with others through teaching, recording, and live performances.

After speaking with pianist and educator Stefan Karlsson on a monthly gig we had together in Dallas, I was convinced that I needed to fight my fears and apply for my master’s degree at UTA (University of Texas-Arlington) where he was then teaching piano. He talked to me about program options and I decided on jazz composition because I really wanted to grow musically in this area. I knew it would be the challenge that I needed to propel me forward to explore my creativity in ways that I thought were potentially too difficult for me.

My Experience at UTA

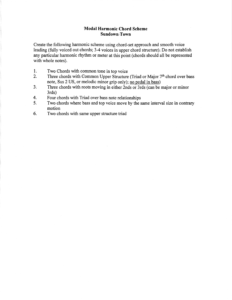

I started studying at UTA in fall of 2018. I was really nervous but proud of myself for taking a leap of faith and trusting that I would eventually land on my feet. I was immediately welcomed in the music department and felt comfortable around my classmates. I felt appreciated and was fortunate enough to know most of the instructors from the local jazz scene which gave me both anxiety and comfort, as I had worked with some in the past. Anxiety that they knew me and expected the very best from me, but comfort in that they were awesome musicians that I knew I could learn a lot from. I studied piano with Stefan Karlsson and Sergio Pamies, jazz history with Brian Muholland, conducting with Tim Ishii, and composition with Dan Cavanagh.

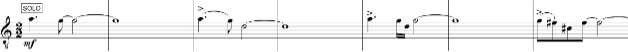

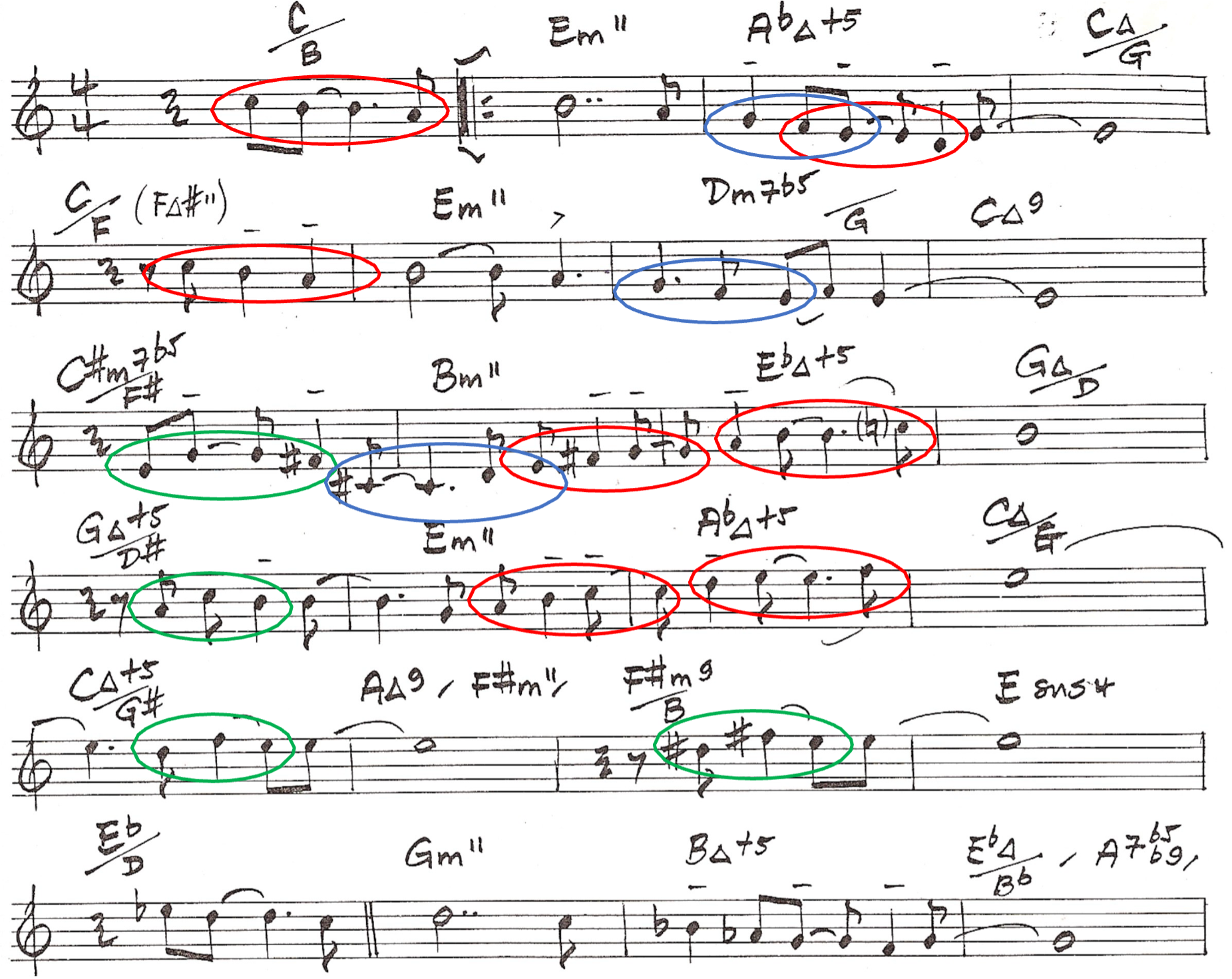

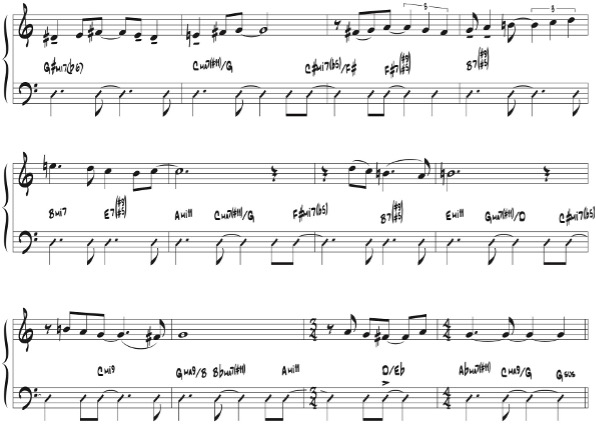

Cavanagh was the department chair and professor over jazz composition at the time. He also taught a course titled “Jazz Style and Analysis” which I took in my first semester. Each week we would discuss the jazz style during an era (using the standard narrative of jazz) and submit 3 transcriptions of choice on our prospective instruments. The course started in the 1920s and ended in the present. We also had to write a short essay and present our written transcriptions to the class while listening to the original recording. Since my primary instruments are voice and trombone, I transcribed several vocal solos until I got to the “post-bop” era where I switched to trombone. At first, I felt like the task was daunting because of the amount of transcriptions and the fact that I was not proficient at writing music on paper quickly. By the end of the course, I certainly got better at transcribing and it made me feel great!

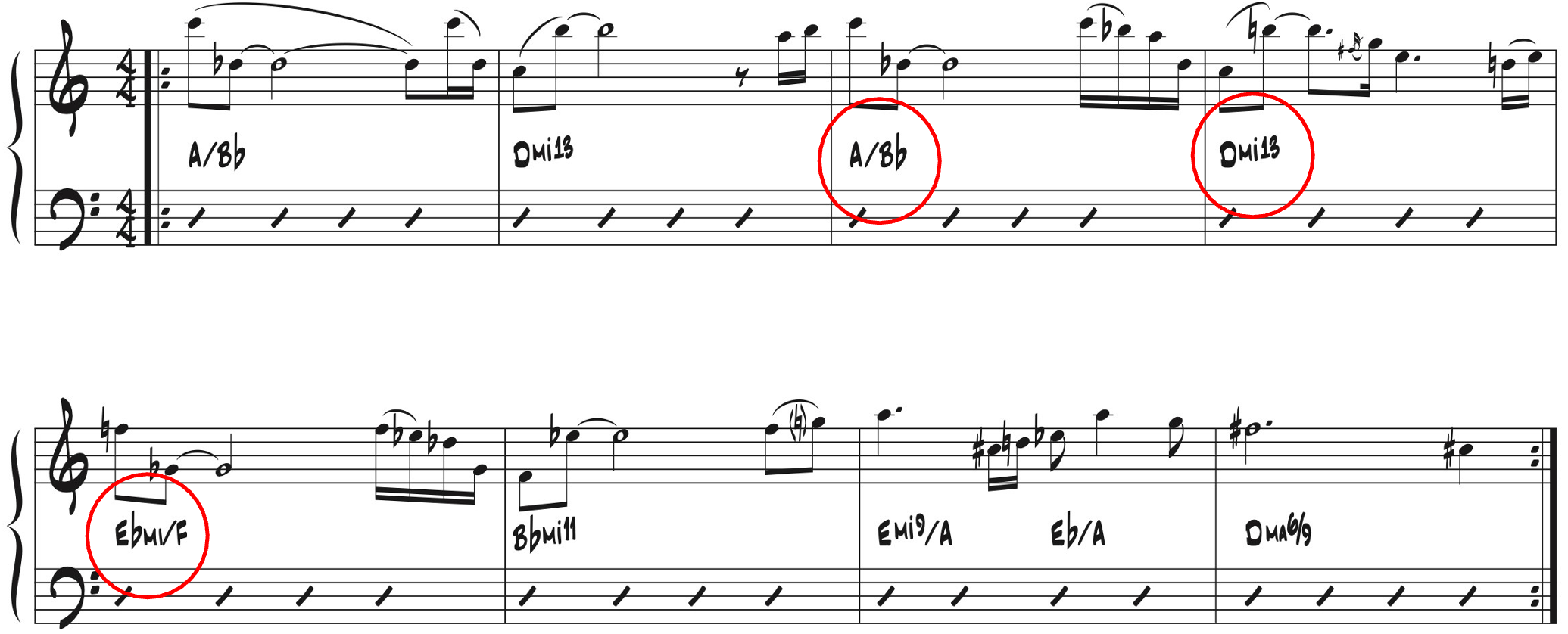

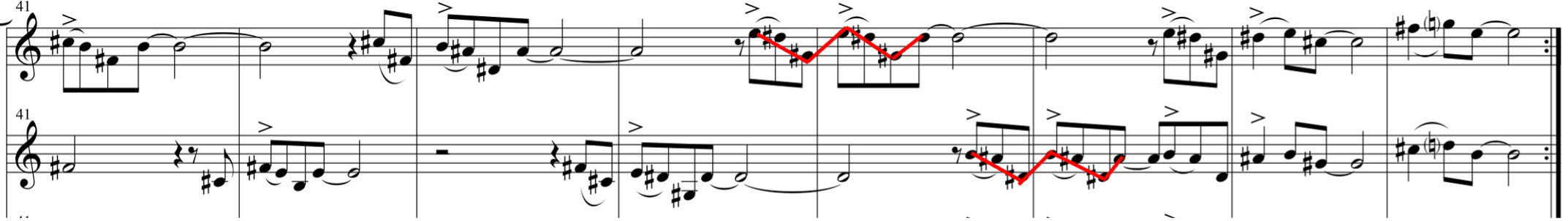

My lessons with Cavanagh were always very open, honest, and full of encouragement. I had done some traditional composition at UNT (small group arranging and big band arranging), but since it was not my primary focus during my undergrad, I had some reviewing and new concepts I needed to get under my belt. I learned new ways to organize my thoughts about composing before even writing a note; I was allowed to always be myself creatively. I explored writing for strings (something I’ve always wanted to do), used different methods for horn voicings, and challenged myself rhythmically while changing time signatures throughout a piece. The difficulty variation was split between the assignments and me. We talked about racism and sexism and the role it’s played in jazz throughout history as well as in academia. We discussed it even more in my “Jazz History and Historiography” class with Brian Muholland. I was told not only that I was the first vocalist in the program, but the first black woman to strive for this degree. It wasn’t until recently that I discovered that I am the first black American to receive this degree. This is an honor I don’t take lightly and am deeply proud of. I find it interesting that there are still “firsts” of this kind in 2020. I hope that it encourages more black musicians to go forth in getting more degrees in jazz on both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

Being Black and A Woman in Jazz

I was taught as a young black child that I had to work 10 times harder to achieve and be noticed in society than my counterparts in order to lead a successful and somewhat comfortable life. Thus, I’ve always put an amazing amount of pressure on myself to be successful in whatever “success” means to me and/or my family. However, I feel even more pressured than ever because of the positive reputation I’ve built both musically and professionally over the years.

As a black woman, musician, composer, and educator it is stressful in ways many don’t or can’t fully understand. I’m in a very marginalized category because I deal with two sides of a difficult coin: one for being black and one for being a woman. Neither those I can change, only people’s perspective of me can. These inferior feelings have almost always bled into how I’ve felt about myself since I can remember. No one ever really told me I couldn’t be great, but societal pressures and subliminal media made me feel this way. On the musical spectrum, there’s often this dismissal from male counterparts on any musical front and on the racial end there’s this assumption that you are probably good but have a bad attitude (“angry black woman” stereotypes). Being a female vocalist also has its own stereotypes that are difficult to break (don’t know any music theory, can’t count off tunes, diva mentality, etc.). In addition, the jazz industry still doesn’t fully recognize women and women of color for their great work and contributions as a whole outside of a handful of great singers and a few pianists. Representation matters and when it isn’t or is rarely there, sometimes it’s hard to stay motivated.

I used Patrice Rushen as a source of compositional and personal inspiration throughout the course of time writing music while at UTA. Her albums Before The Dawn (1975) and Patrice (1978) are my favorites because they’re a mix of straight ahead, soul, and funk, styles that fit my mindset and musical interest. She is an amazing composer and songwriter with the piano chops and voice to match. I did a lot of research of her and her career and hope to one day make the type of mark she’s made on me on other women in the jazz community. I also appreciate the compositions and arrangements of trombonist and composer/arranger Melba Liston and the contemporary eclectic style of Esperanza Spalding’s work. Other strong compositional/arranging influence came from Duke Ellington, Quincy Jones, and Herbie Hancock.

Pandemic Effects, Protests and Life Transitions

COVID-19 hit in March, right in the middle of the semester as I was to begin to finish my last few pieces for my recital. When everything shut down, so did I. I was already having some writers block happening shortly before, but the pandemic completely closed me up creatively. It was then I knew I needed to allow myself time to process, focus, and heal so that I could finish the rest of my required work.

Prior to the pandemic, I was teaching and gigging while attending school. So, that meant going back and forth between Cedar Valley and UTA sometimes on the same day. One semester I was even an adjunct instructor at UNT also. It was insane and a little too demanding but I still had to work. I got engaged in October of 2019 and began planning my wedding with my now husband. My master’s recital was set for April. I was going to graduate in May and we would be married in June on Juneteenth. I had planned to travel with friends to Jamaica for 4 days and go back to China to teach at a jazz summer program for 2 weeks and perform.

While we are here we are in the middle of the worst pandemic since the 1918 Spanish Flu, the tragic and unnecessary murder of George Floyd happens due to a police officer kneeling on his neck for almost 9 minutes. As if we aren’t dealing with enough collectively as a nation, this becomes the new focus. When the news of this reached me, I was immediately outraged and sick to my stomach. I thought about all the other black men and women who had been killed in recent weeks and years from police and/or racist violence: Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Botham Jean, Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, and so many others. I thought about when I wrote the protest song “Freedom” on The Next Chapter with my friend musician/producer Jemarcus Bridges and poet Rodderick Parker about some of these very killings. My heart was and still is broken and tired. However, seeing people take to the streets to demand justice for George Floyd and the others who have lost their lives gave me a bit of hope for continued resilience like that seen from the 1950s-60s Civil Rights Movement. Despite the pandemic and social injustice fight currently, I find a little bit of peace seeing that there may be some real change happening and from knowing we are all in this together.

I’ve recently started to put pen to paper again charting new ideas about how to express my feelings forwardly and creatively that not only sheds light on this issue, but also leaves hope.

Listening to “Search For The New Land” by Lee Morgan and “Fables of Faubus” by Charles Mingus are just 2 compositions that came to mind to draw from.

What I Learned Getting Through A Master’s Program

Studying jazz composition at UTA opened my eyes to many new ways to think about constructing harmony and organizing musical ideas. I also learned a lot about myself; I’m much more resilient than I thought and I can now write for different types of instrumentation. I enjoyed singing big band tunes with the jazz orchestra, learning how to research a topic and write about it, and speak with my professors about their careers as educators and gigging musicians. I even dug deeper into my roots as a black American and what that means to the music I hold dear and to society. UTA summer jazz camp was where I began my jazz educational journey when I was a teenager so it’s funny how life comes full circle sometimes. Overall, my time at UTA was memorable and special. A time period I will look back on with gratitude and a bittersweet smile.

About the Author:

Refreshing and beautiful are how many have described the voice and persona of Tatiana “LadyMay” Mayfield, a jazz vocalist, musician, composer, and educator from Fort Worth, Texas. “LadyMay” (as she has been named) has been singing and playing jazz music since the tender age of thirteen. Since then, she has performed in various venues and festivals throughout the U.S. and abroad, which in turn have earned her rave reviews from listeners and musicians in addition to numerous awards.

In 2017, “LadyMay” was awarded 2nd place in the Sarah Vaughan International Jazz Vocals Competition held at NJPAC in New Jersey. In that same year, she received the “Jazz Innovators Award” from Dallas, TX as part of Jazz Appreciation Month for her contributions to jazz education for young people in the Dallas/Ft. Worth area. Mayfield was also chosen as one of the twelve semi-finalists to compete in the prestigious 2010 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Vocals Competition that was held in Washington, D.C before a legendary panel of judges. In the summer of 2019, the city of Fort Worth awarded her with a “Legend In The Making” award at their annual “Dr. Marion J. Brooks Living Legends Awards” for her accomplishments in entertainment and education. In addition to several other awards, she is also a 2006 YoungArts winner for Jazz Voice. She has also appeared on Dallas/Ft. Worth’s news television show WFAA “Good Morning Texas” four times since 2011. Mayfield has opened for several well-known artists such as Kirk Whalum, Will Downing, Randy Brecker, Dave Valentin, Bobbi Humphrey, and The Main Ingredient. LadyMay has also performed in 3 concerts between 2016-2018 with the legendary Cincinnati Pops Orchestra. The first concert was a tribute celebrating African-American women in music entitled “I’m Every Woman”, then again for their Independence Day “Patriotic Pops: Celebrating the 75th Anniversary of the USO”, and as of late in the “Classical Roots: Under One Roof” concert honoring the diverse history of the historic Music Hall where they perform. Mayfield has also performed with the Hilton Head Symphony Orchestra in South Carolina in the spring of 2018.

“LadyMay” has recorded three albums, From All Directions (2009), A Portrait Of LadyMay (2012), and The Next Chapter (2018). The first album From All Directions was recorded while she was still attending the University of North Texas, where she received her degree in Jazz Studies. Jazz journalist Scott Yanow described her voice on her debut album From All Directions (2009) as “attractive” with “excellent elocution” and a “joyful spirit”. On her sophomore album A Portrait Of LadyMay (2012), Harvey Siders, former writer of JazzTimes and Downbeat magazines, describes her intonation as “flawless” and her scatting “as natural as breathing.” In addition to her vocal skills, she plays piano, trombone, composes, and teaches voice and music theory. In May of 2017, she was awarded 3rd place in the “Performance” category of the International Songwriting Competition for her original song “Forgive Me Someday” from her latest album The Next Chapter.

LadyMay’s appeal has also reached listeners abroad in the UK, Switzerland, Germany, France, Nigeria, and Brazil. Her music has been featured on several international radio stations such as “Solar Radio”, “Jazz FM”, “Tropical FM”, and “Premier Gospel Radio” in the UK, “RJM Radio” in France, and “Smooth 98.1” in Nigeria. In November 2012, her song “Real” from A Portrait Of LadyMay reached #1 on the “UK Soul Chart”. In July of 2013, she completed her first tour (LadyMay In The UK) to London where she was widely received on radio appearances, as well as at some of their top performance venues such as Ronnie Scott’s, Pizza Express in Soho, and the Flyover Portobello. UK based record store “Soul Brother Records” labeled “A Portrait Of LadyMay” as one of their “Best New Jazz Releases of 2013”. As an educator, Mayfield is an adjunct professor of commercial voice at Cedar Valley College in Lancaster, TX and has previously taught jazz voice for the University Of North Texas in Denton, Texas. In 2019, she taught in Zhuhai, China for the Golden Jazz Henquin Jazz Week and performed in the “Crossing Music and New Generation Jazz Festival”. Mayfield has a bachelor’s degree in jazz studies from the University of North Texas (Denton, TX) and a master’s degree in jazz composition from the University of Texas at Arlington.

For more information on Tatiana “LadyMay” Mayfield, visit www.tatianamayfield.com.

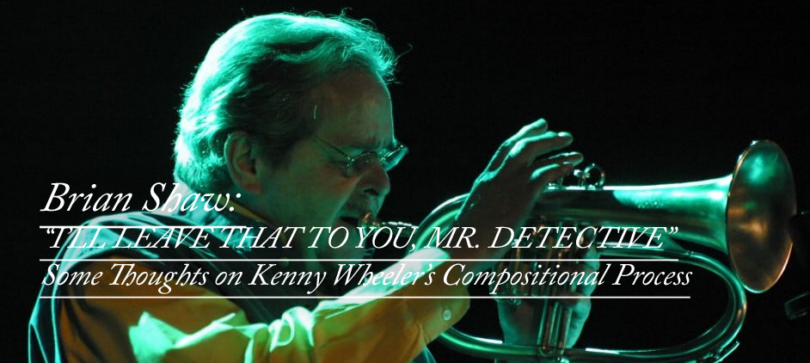

Brian Shaw is an active performer, arranger, and educator known for his versatility. He is one of the few trumpet players in the world equally comfortable in early music, orchestral, jazz, and commercial settings on modern and period instruments. He has released four albums as a soloist, and is principal trumpet with the Dallas Winds, Santa Fe Pro Musica, Spire Baroque Orchestra, and is a core member of the Pacific Northwest Ballet orchestra. A former Banff Centre student of Kenny Wheeler’s, Brian published a book of his solo transcriptions in 2000 and co-authored his biography Song for Someone (released 2025) with Nick Smart. He regularly teaches Baroque trumpet at the Eastman School of Music and was Professor of Trumpet and Jazz Studies at Louisiana State University for 15 years. He lives near Seattle with his wife Lana, their sons Thomas and Elliot, and their family dog Ernie.

Brian Shaw is an active performer, arranger, and educator known for his versatility. He is one of the few trumpet players in the world equally comfortable in early music, orchestral, jazz, and commercial settings on modern and period instruments. He has released four albums as a soloist, and is principal trumpet with the Dallas Winds, Santa Fe Pro Musica, Spire Baroque Orchestra, and is a core member of the Pacific Northwest Ballet orchestra. A former Banff Centre student of Kenny Wheeler’s, Brian published a book of his solo transcriptions in 2000 and co-authored his biography Song for Someone (released 2025) with Nick Smart. He regularly teaches Baroque trumpet at the Eastman School of Music and was Professor of Trumpet and Jazz Studies at Louisiana State University for 15 years. He lives near Seattle with his wife Lana, their sons Thomas and Elliot, and their family dog Ernie.