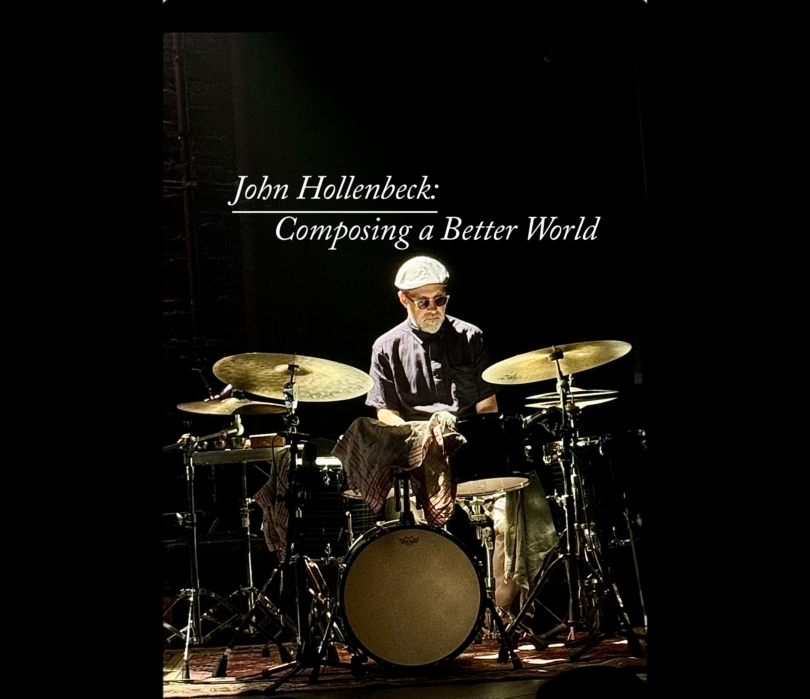

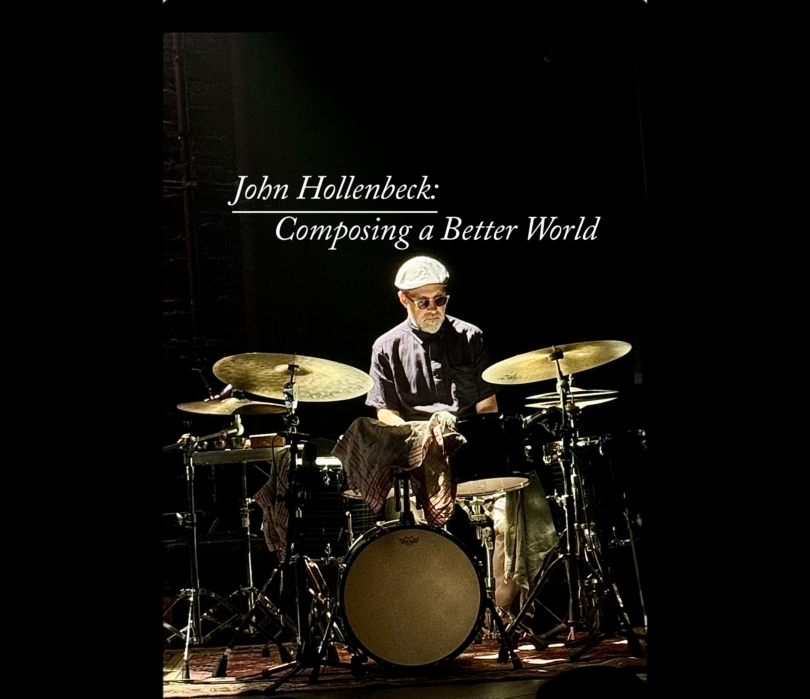

John Hollenbeck explores how the decisions during the composition process change the composer themselves and why that is important today.

John Hollenbeck explores how the decisions during the composition process change the composer themselves and why that is important today.