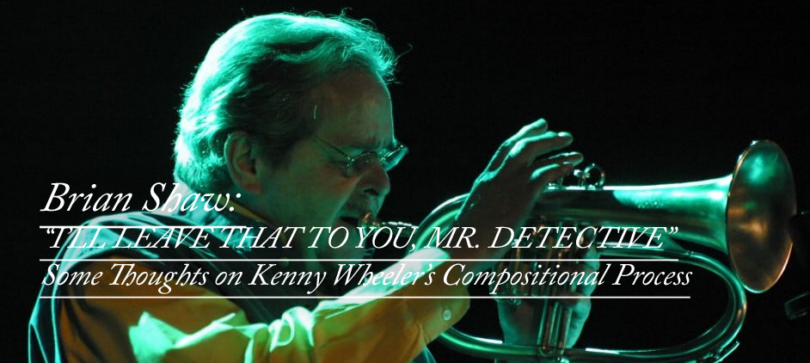

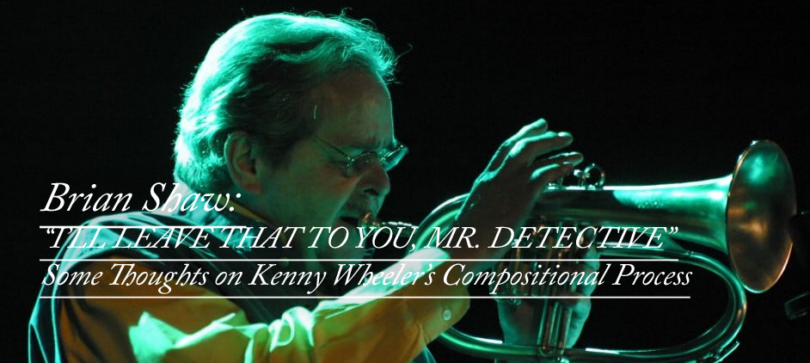

Brian Shaw discusses Kenny Wheeler’s compositional techniques and history and how that might have inspired writing techniques and his sound.

Brian Shaw discusses Kenny Wheeler’s compositional techniques and history and how that might have inspired writing techniques and his sound.