I am honored to have this opportunity to share some of my thoughts on what guides my practice as a composer and the types of strategies I have used. All my thanks to JC Sanford and Jim McNeely for thinking about me as a potential contributor to this ISJAC artist blog. Since I am probably not someone whose work most of you are familiar with, I really appreciate the chance to introduce you to some of my music within the context of this presentation.

In my own composing and when working with students, I often use a variety of conceptual exercises or problem-solving approaches that can lead to a different kind of envisioning and help move away from those comfortable habits we might fall into. I tend to find inspiration from a wide variety of methods that are both musical and non-musical. Some of these might include:

- The Sounds and Colors of Modality

- Melodic Lyricism

- Going to Rhythmic Places

- Using Freer Approaches to Music-Making

- The Bigger Picture: Life Experiences, Spirituality & Social Consciousness

However, the driving force behind all of this is the understanding that I am writing with the listener in mind.

Connecting with the Listener

When writing, I am always trying to find ways to forge a relationship with the listener and engage with them on some level. While it might sound a little strange, I don’t really write specifically for a “jazz” listener in mind. I am actually thinking more about the everyday or general listener – someone that may be coming to the listening experience with a lack of familiarity with or exposure to jazz or music that involves a more active listening approach. With that said, I try to find ways to bring them into the music by connecting with them or meeting them where they are in order to provide them with a feeling of participation.

We all tend to listen to music in different ways and for different reasons, and we listen from many perspectives and levels of engagement. As composer Aaron Copland notes in his book What to Listen for in Music (1939/1967), “Besides the pleasurable sound of music and the expressive feeling that it gives off” (references to his concepts of the sensuous and expressive planes of music listening), it is on the sheerly musical plane “where music exists in terms of the notes themselves and their manipulation.” Here, we consider how such elements as melody, harmony, timbre, rhythm, and form are used in a piece of music. Now, musicians can find themselves a bit preoccupied with this level of listening and often have the inclination to be too analytical when interacting with the music. If we examine the experience of the general listener on this same plane, they are usually quite comfortable connecting with the elements of melody and rhythm because they can identify with them more than the others. If you think about it, we are essentially conditioned from a very young age to interact with music through singing melodies and recognizing melody within a song. Consequently, melody is the means by which most people seem to relate to music.

Rhythm, I would offer, is what listeners often respond to in a very physical or visible way when experiencing music. When we perceive rhythm, we do so with the help of patterns of sound occurring over time that can serve as a source of organization. Rhythm can also be a “kinesthetic thing” that can trigger the listener to interact with what they are hearing through movement. This might be due to the sensation of particular rhythmic groupings or how meter is used or the feeling of “groove” they are connecting with.

Recognizing the power that melody and rhythm can have when it comes to reaching and bringing all manner of listeners into our musical world, my writing aims to explore lyrical melodic content within different types of modal and non-harmonic settings; musical ideas with strong rhythmic identities; and the utilization of groove with its infectious nature. I also use tone rows and pitch sets, but try to put all of these techniques into practice in meaningful, “bigger picture” ways.

Modal Approaches

My introduction to the world of modal harmony changed my thinking and my approach to creating music forever!! Though I had already found these sounds appealing and thought-provoking when I was in high school and college, I really didn’t know how to make sense out of what I was hearing, which was so different from the bebop-derived music I had been checking out during this period. It was when I attended the University of Miami Frost School of Music for the master’s program in jazz pedagogy that I had the chance to study with composer Ron Miller who helped me develop a better understanding of the music from multiple perspectives and who constantly inspired me!!

I find there are so many conceptual positives when using the modal harmonic language. First of all, there is a certain sense of freedom that seems to automatically accompany its use. When it comes to organizing the flow of chord progression movement, modal harmony doesn’t require the use of the types of restrictive chordal root movement that are driven by the dominant-to-tonic relationship found in functional harmony (i.e. V7-I; ii-V7-I; iii-VI7-ii-V7, etc.). With that said, the bass motion can now be more melodic in character and less functional in the traditional sense.

I also view the modal language as one that facilitates a more visual approach to creating music. The spectrum of modal harmonies, which are derived from the major, ascending melodic minor, harmonic minor, harmonic major, and melodic minor #5 parent scales (as well as the use of non-harmonic, symmetrical scale systems) offers a range of colors to draw from and, subsequently, the ability to imagine creating music from a more visual or cinematic perspective.

In addition, this approach has the added benefit of making use of the types of “moods” that can be associated with certain modal chord colors as a way of organizing the compositional flow and intent (i.e. hearing Phrygian as “mysterious,” Ionian as “relaxed, peaceful, soothing,” Lydian-Augmented as “quite aggressive or frantic/panicky”; of course these can all be seen as subjective descriptions as there will frequently be different kinds of mood associations and the context in which these sounds appear will also impact one’s perception). The modal approach also offers a very flexible harmonic language that is adaptable for use with many music genres or styles (classical, Latin, contemporary popular music, funk, Brazilian, R&B) in addition to jazz.

Finally, it promotes individuality of expression, accommodates both lyrical and virtuosic writing sensibilities, encourages experimenting with form and flow, and can undoubtedly add to one’s harmonic/melodic palette as a composer and improviser. A wonderful resource that I find to be most empowering is Ron Miller’s Modal Jazz Composition & Harmony (Volumes 1 & 2) from Advance Music!!

I would like to share two examples of my writing that take place in modal harmonic settings. The first, “Many Roads Beneath the Sky,” is actually a piece where the melody came to me in a nearly completed form almost immediately after I sat down at the piano and began exploring (this is not usually the case with me!). In this instance, it was the melody that would go on to determine the modal harmonic framework.

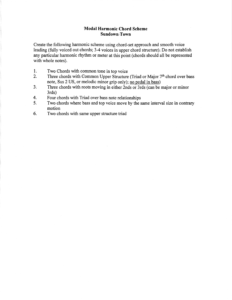

The second example, “Sundown Town,” was shaped by written directions for creating a modal harmonic scheme to be used to guide the realization of the harmonic progression for this piece. The melody and development of the composition’s formal structure (see Example #3) came later. I also use this approach with my students in an effort to offer guidance on creating progressions for writing projects. Interestingly, what I have found here is that ten students could use the exact same text description and the result will be the realization of ten completely different works (I mean, no two pieces are ever similar!!). The title of this composition refers to the segregated “sundown towns,” in which a municipality or neighborhood in the United States was intentionally all-white and excluded people of color who were met with intimidation, discriminatory laws, and violence. The term is derived from posted signs warning people of color to leave the town by sundown.

Rhythm & Groove

In my own writing, as I have shared earlier, it’s all about rhythmic engagement in an effort to connect with the listener and allow them to feel like a participant in this process. To accomplish this, I am always considering such notions as groove, rhythmic interaction, rhythmic identity, using metric variety to play with the listener’s expectations, and that potential kinesthetic impact – making the body want to move!

“Let’s Conversate” was strongly influenced by the infectious spirit of funk music, which was so much a part of my life as a teenager and young musician when coming up. It is a composition that is conversational in nature and highlights the independence of musical voices, each with its own story to tell, which interact with each other in musical dialogue. The piece is based on two tetrachords that, when linked by a whole step, create the seventh mode of the harmonic minor scale, which is known as the “Altered bb7 mode” (this involves both the “Spanish Phrygian” tetrachord = C-Db-Eb-Fb and the “Hungarian Minor” tetrachord = F#-G#-A-C). It was also inspired by the concept of minimalism and the use of specific pitch collections for constructing melodic material, piano voicings, and bass lines (all of which are comprised of notes from the aforementioned scalar pitch set).

The composition incorporates displaced rhythmic stress to provide a sense of uncertainty as to the actual meter or “groove” being used. It is largely organized around 7/4 meter (4/4 + 3/4) for the introduction, exposition, and the tenor saxophone/trombone N.C. (No Chord) solo exchanges. However, a slightly altered bass line is introduced during this solo section that was meant to move the listener away from the original metric subdivision pattern to now emphasize a much different subdivision of 4/4 + 3/4 + 4/4 + 3/4 + 4/4 + 2/4 + 4/4 + 4/4. The tenor saxophone/trombone phrase trading then leads to a collective improvisation in a “Crazy Frenetic Madness” section in 4/4 – an even more tense and dissonant polychordal area that involves three superimposed chord structures (Ab minor/major 7 over Gb minor/major 7 over Eb major), which would not really be considered the traditional way of achieving release from tonal tension. A contrast in meter is introduced for the piano solo (moving to 4/4) as well as a different bass line; this solo also culminates in the “Crazy Frenetic Madness” section.

Composing Using Tone Rows

I also like to challenge the listener to step outside of their comfort zones, but in doing so, I always try to ground that experience with some sort of interaction with the areas they may be most comfortable with – melody/lyricism and rhythm. A good example of this would be my composition “Placeless” from the upcoming What Place Can Be For Us? release on Origin Records. The melody is based on a series of 12-tone rows with the exception coming at the end of the melodic exposition where a pitch set of six notes is repeated several times as part of a melodic motive (see Example #8). While this may sound super academic and a recipe for a dry musical offering, it is the angular funk vibe and feeling of shifting rhythmic grooves based on phrases that are asymmetric in length that serves the purpose of meeting the listener where they are, catching their attention, and bringing them into this musical experience.

Pitch Sets

In addition to tone rows, I use pitch sets or smaller groupings of pitches (as was recently mentioned) and then manipulate that material through inversions, retrograde, and shuffling sets. I also play around with rhythm in similar kinds of ways by creating rhythmic sets and using retrograde to reimagine rhythmic patterns. Sometimes in these cases, the harmonic foundation might be modal in flavor with “Dance Like No One is Watching” from the Uppity recording and “Joy” and “Loving Day (June 12)” from the recording Beauty Within, as examples of this. However, I still try to approach all of this with a strong sense of melodic lyricism and rhythmic awareness in mind; even if you might hear some crazy kinds of ideas “up in there.”

The Bigger Picture: Life, Spirituality & Social Consciousness

Putting techniques into practice in meaningful ways

My work as a composer also explores issues of social consciousness and addresses themes of social justice, equality, race, intolerance, hate, prejudice, gender, ethnicity, humanity, politics of representation, spirituality, and “place” in society, all in an effort to provide opportunities for all of us to gain a deeper awareness and understanding of these issues, each other, and ourselves.

In recognition of a significant legal ruling that impacted my family in profound ways, I wrote the composition “Loving Day (June 12),” which is named for the day in 1967 when the Supreme Court of the United States effectively struck down the anti-miscegenation laws that existed in sixteen states. The case before the court, “Loving vs Virginia” involved the interracial married couple of Mildred and Richard Loving who were subsequently arrested and forced to move out of Virginia. The Lovings brought the case to then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and it was later referred to the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union), which represented them. Several years later, the Supreme Court unanimously voted the law unconstitutional. This composition is dedicated to my grandparents John & Mary Hulnik who were, respectively, of Polish and Trinidadian descent, and who helped raise me from the late 1950s until the end of the 1970s. I also dedicated this piece to my Uncle Mervyn Guy Carmichael & Aunt Rita Carmichael, who were from Trinidad and Germany.

The upcoming What Place Can Be For Us? release is a 10-movement suite that speaks to notions of “Place” and the overarching issues of inclusion, belonging, place as an emotional space of being, finding one’s place in a socially stratified society, as well as circumstances of exploitation and zones of refuge experienced by people of color and other global citizens.

“Sunken Place” is a composition inspired by Jordan Peele’s critically acclaimed film, “Get Out” and his reference to the sunken place. In the words of Peele it is: “the system that silences the voice of women, minorities, and of other people…the sunken place is the President (Trump) who calls athletes sons of bitches for expressing their beliefs on the field…Every day there is proof that we are in the sunken place.” In a statement made on Twitter, Peele explained, “the Sunken Place means we’re marginalized. No matter how hard we scream, the system silences us.”

As we all know, composing is a multifaceted activity with so many ways available to us to awaken our creative thoughts and actions beyond those I have shared. Yet, I do hope some of the approaches presented here manage to resonate and possibly inspire you in some small way. These are strategies that have served as sources of stimulation and have opened up the creative process for me while also helping me to move away from those predictable or comfortable habits I would fall into when composing. Thanks so very much for reading and for listening to the music!!

About the Author:

Composer, conductor, and bandleader Anthony Branker is an Origin Records recording artist who was named in Down Beat magazine’s 63rd & 62nd Annual Critics Poll as a “Rising Star Composer.” Dr. Branker has eight releases in his fast growing and musically rich discography that have featured Ralph Bowen, Fabian Almazan, Linda May Han Oh, Rudy Royston, Pete McCann, David Binney, Conrad Herwig, Jim Ridl, Kenny Davis, Donald Edwards, Mark Gross, Tia Fuller, Steve Wilson, Antonio Hart, Clifford Adams, Andy Hunter, Bryan Carrott, Eli Asher, Jonny King, Freddie Bryant, John Benitez, Belden Bullock, Adam Cruz, Ralph Peterson Jr., Wilby Fletcher, Renato Thoms, Alison Crockett, and Kadri Voorand.

In 2023, Origin Records will reissue Branker’s Spirit Songs project featuring drummer Ralph Peterson, Jr. and release his most recent project What Place Can Be For Us? – a 10-movement suite that speaks to the overarching issues of inclusion, belonging, place as an emotional space of being, as well as circumstances of exploitation and zones of refuge experienced by people of color and other global citizens. It will feature tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, trumpeter Philip Dizack, alto & soprano saxophonist Remy Le Boeuf, guitarist Pete McCann, pianist Fabian Almazan, bassist Linda May Han Oh, drummer Donald Edwards, and vocalist Alison Crockett.

Branker was a Third Place Winner in the 2021 International Songwriting Competition (ISC) in the jazz category, has received commissions, served as a visiting composer, and has had his music featured in performance in Poland, Italy, Denmark, Finland, France, Estonia, Russia, Australia, China, Germany, Lithuania, and Japan. During his residency at the Estonian Academy of Music & Theatre in Tallinn, Branker composed The Eesti Jazz Suite, a five-movement work inspired by the culture and the spirit of the people of Estonia. The work was premiered in 2006 at the academy of music as part of the concert tour of the Princeton University Jazz Composers Collective, which was sponsored by the Department of State of the United States, the U.S. Embassy in Estonia, and the Estonian Academy of Music. Dr. Branker’s works have also been performed and/or recorded by the New Wind Jazz Orchestra, Sylvan Winds with Max Pollack Dance Ensemble, Composers Concordance Big Band, Princeton University Orchestra, Rutgers University Jazz Ensemble, and the Rutgers Avant Garde Ensemble.

Dr. Anthony Branker was on the faculty at Princeton University for 27 years, where he held an endowed chair in jazz studies and was founding director of the program in jazz studies until his retirement in 2016. Currently, he is on the jazz studies faculty at Rutgers University Mason Gross School of the Arts where his teaching responsibilities include graduate and undergraduate courses and ensembles. Branker has also served as a U.S. Fulbright Scholar at the Estonian Academy of Music & Theatre and has been a member of the faculty at the Manhattan School of Music, Hunter College (CUNY), and Ursinus College.