Artist Blog

Writings by new and established artists

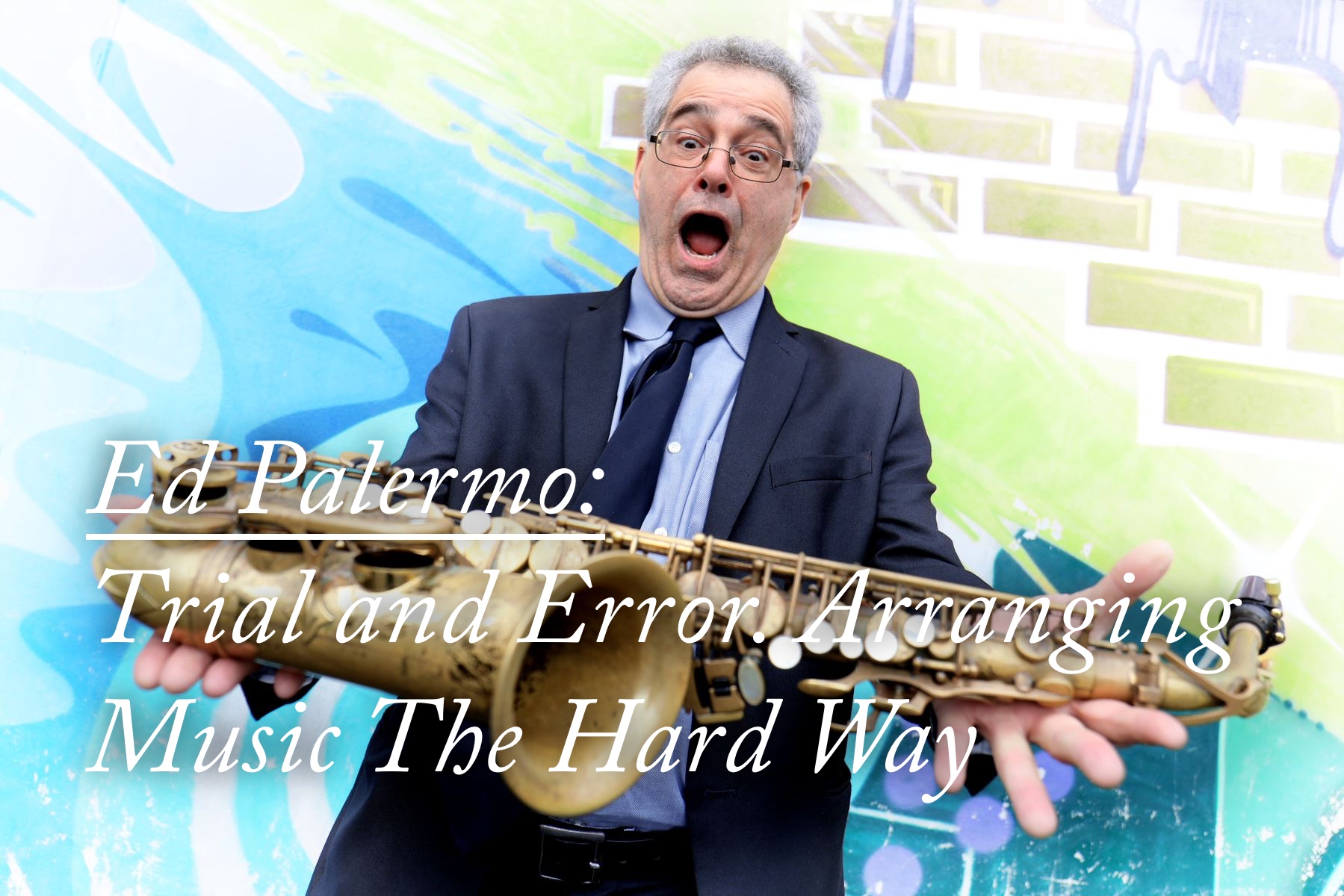

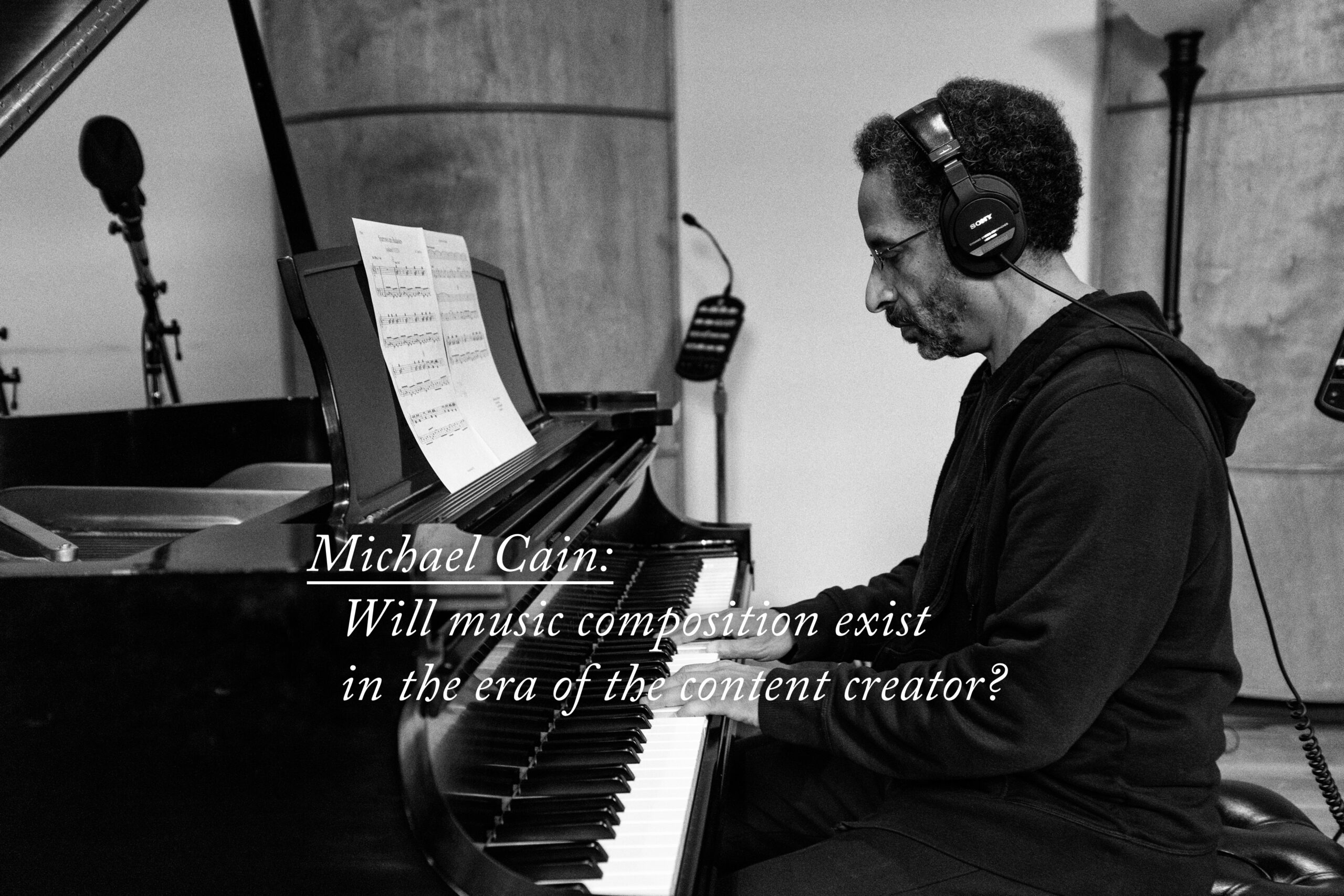

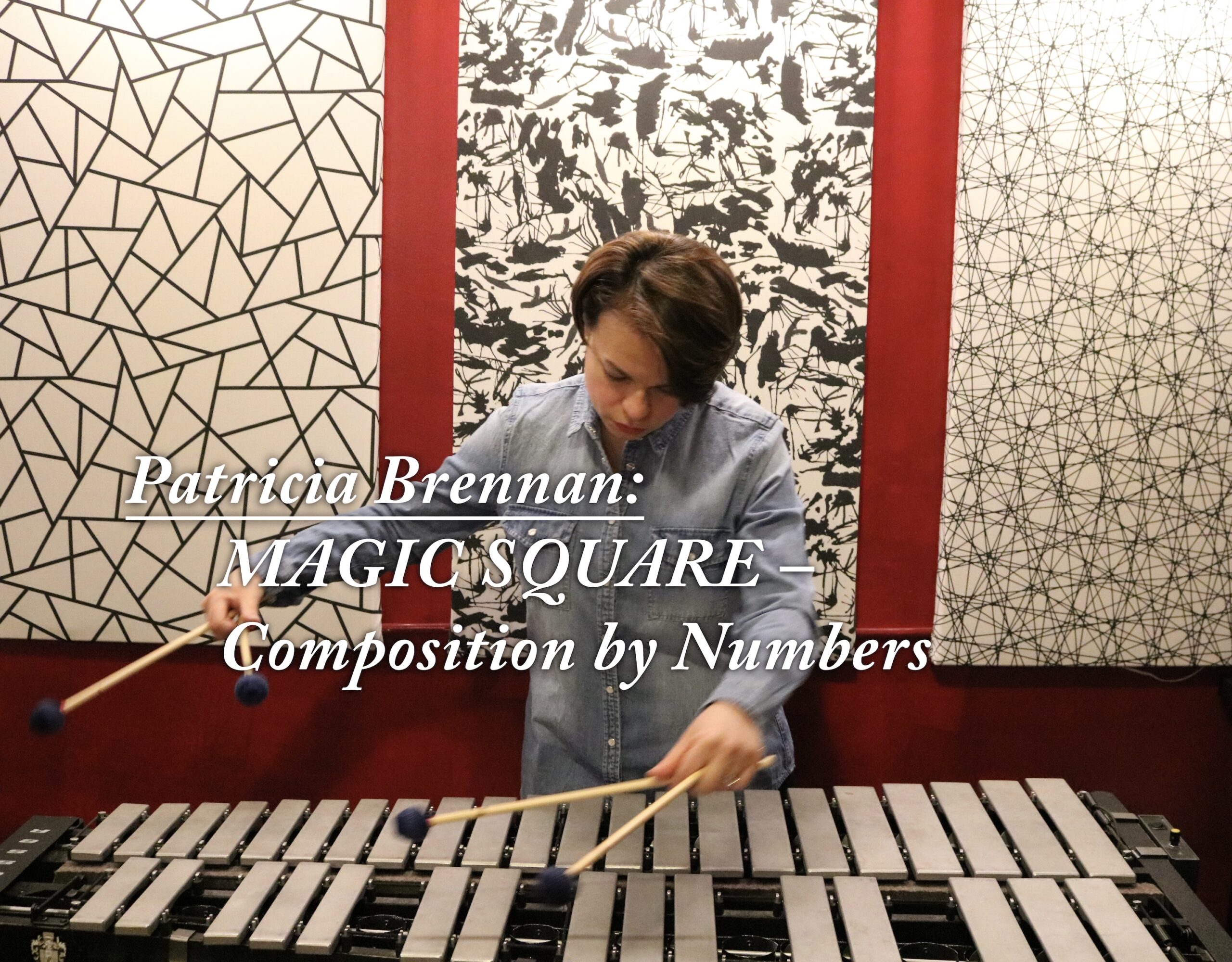

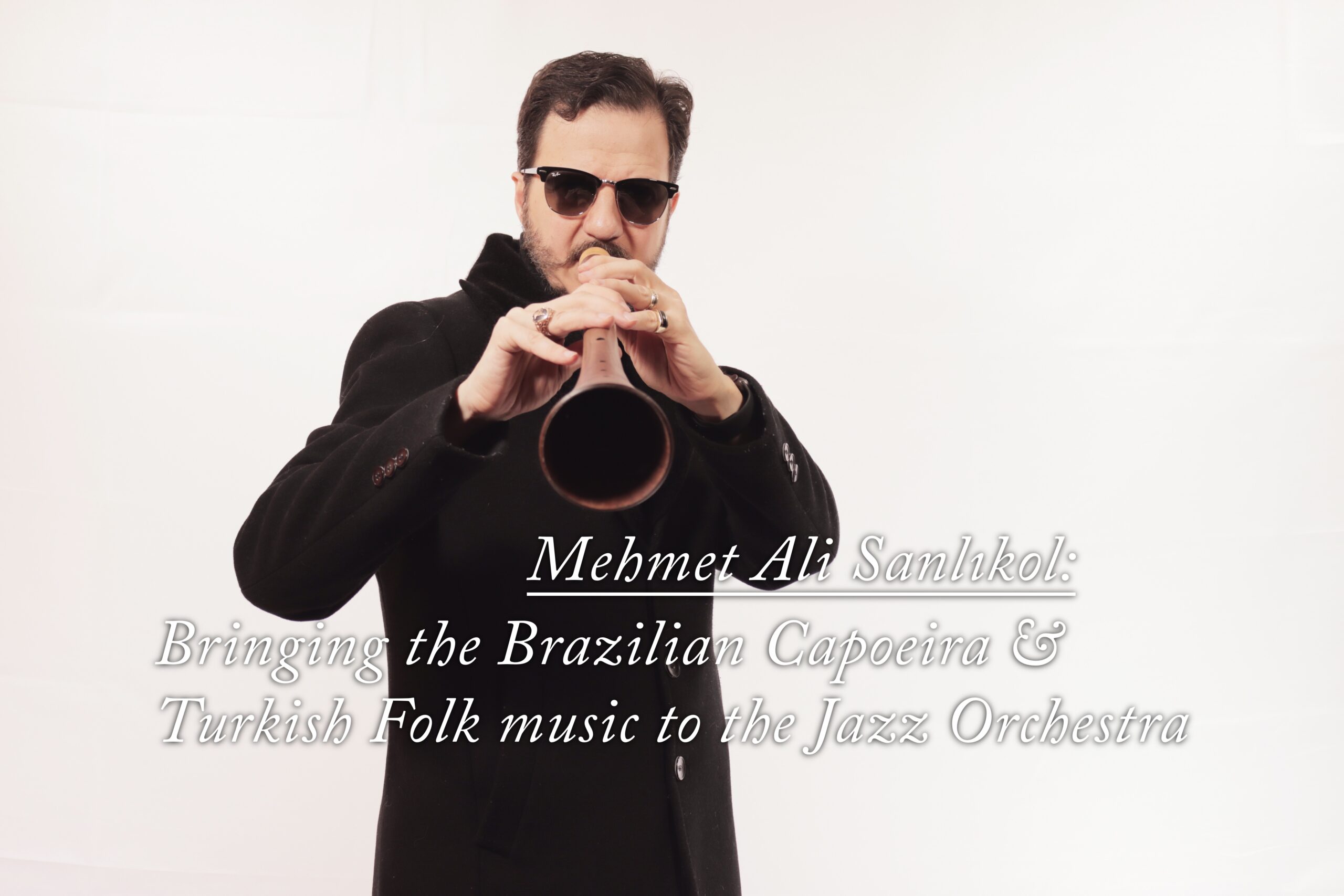

Featured This Month

Managed and curated by trombonist and composer JC Sanford, the ISJAC Artist Blog is a collection of writings by some of the most visionary minds in the jazz composition and arranging community. Featuring articles by composers from all walks of the industry, the ISJAC Artist Blog is updated monthly with both new and archived pieces.

Our two most recent articles are always available on the ISJAC site, with the full archive accessible for our member community.

Not a member yet? Join today!

The Archive

© Copyright ISJAC. All Rights Reserved